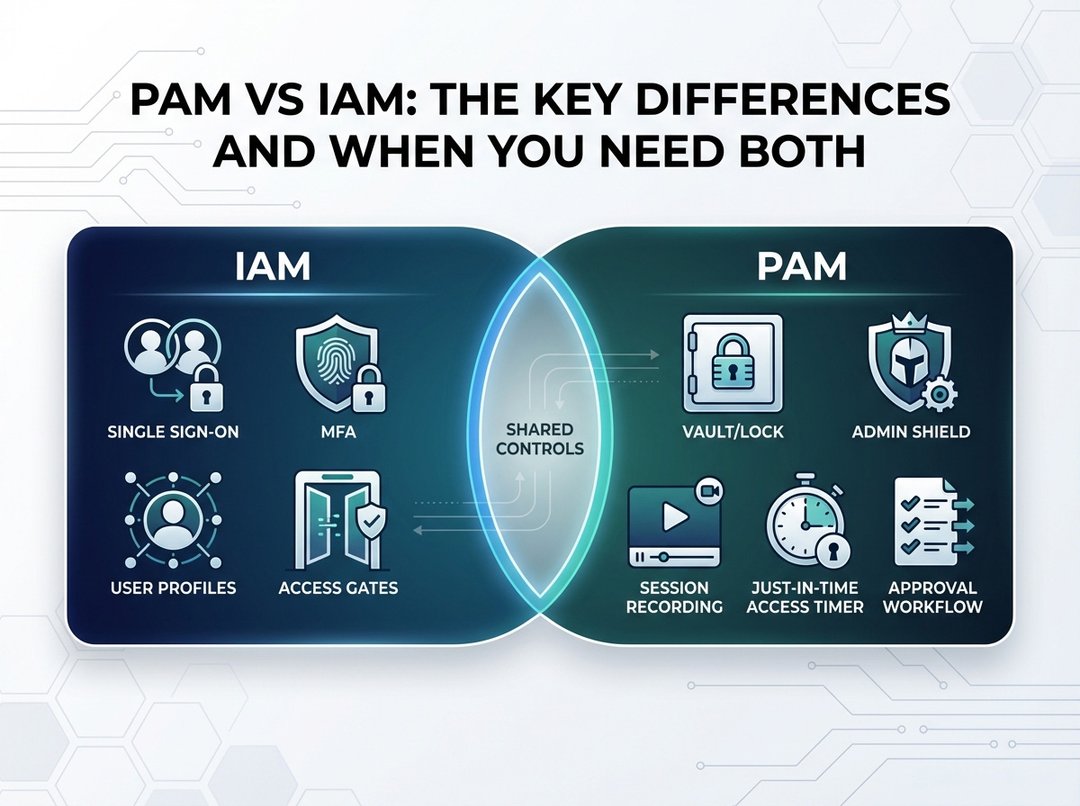

PAM vs IAM in one sentence each

IAM (Identity and Access Management) answers a broad question: who is this user or system, and what should they access? In practice, IAM covers sign-in, multi-factor authentication, single sign-on, user provisioning, and policies that decide whether access gets approved. It organizes access at scale, so the company can stop managing permissions app by app.

PAM (Privileged Access Management) answers a narrower but more dangerous question: how do we control and prove what happens when someone holds admin power? PAM focuses on privileged accounts, elevated sessions, secret rotation, approvals, and audit evidence. It treats administrator capability like handling hazardous materials: you want tight containment, clear labeling, and a paper trail.

Why PAM vs IAM matters: two threat models, two failure modes

If you only remember one idea, make it this: IAM tries to prevent the wrong person from getting in. PAM tries to reduce the damage when someone with power does something risky. Those are not the same problem.

IAM’s main failure mode looks like this: a user gets phished, an attacker logs in successfully, and the attacker inherits whatever standing access that identity already had. That scenario often starts with weak MFA, reused passwords, or overly broad groups. It also happens when offboarding fails and old accounts quietly remain active.

PAM’s failure mode is different and usually louder. Someone obtains admin-level capability, then they change production, disable logging, exfiltrate a database, or create backdoor accounts. Sometimes the “someone” is an attacker. Sometimes it is a legitimate employee who made a bad call under pressure. Either way, privilege converts mistakes into outages and converts intrusions into incidents.

Consequently, PAM vs IAM is not a “which tool wins” debate. It is a question of which layer addresses which risk.

PAM vs IAM: the key differences (conceptual and technical)

Scope: broad access versus high-impact access

IAM typically touches everyone. It covers employees, contractors, and sometimes customers. It also touches hundreds of applications. It aims for consistency and speed because the business cannot wait three days for access to email.

PAM targets a smaller group and a smaller set of systems. It concentrates on administrators, operators, and automation identities that can change infrastructure state. It optimizes for safety and proof, not convenience.

Credential handling: tokens and federation versus secrets and sessions

Modern IAM often relies on federation like SAML or OpenID Connect. Users sign in once, then they receive tokens that applications trust. That approach reduces password sprawl and centralizes policy.

PAM tends to handle the messy parts IAM does not want to touch. That includes shared admin passwords, SSH keys, local administrator accounts, service credentials, and sensitive API keys. Strong PAM also brokers sessions, so users do not directly handle the secret at all. They request access, then the system opens a controlled session to the target.

Time: standing permissions versus just-in-time privilege

IAM frequently grants ongoing roles. That works for stable job functions, yet it also creates “permission fossil layers” where access accumulates for years.

PAM pushes the opposite idea: privilege should expire by default. Just-in-time elevation means a user receives admin capability for a short window, then the window closes automatically. This design reduces the chance that an attacker can reuse stale admin access later.

Evidence: logs versus forensic-grade visibility

IAM logging typically shows authentication events, sign-in risk signals, and authorization decisions. That data helps answer “who accessed what” at a system level.

PAM often needs to answer a sharper question: “what did they do with admin power?” That drives controls like session recording, command auditing, ticket correlation, and tamper-resistant audit trails. Those features matter when you must reconstruct actions quickly during an incident.

Where IAM and PAM overlap and why people confuse them

Both domains use familiar concepts like role-based access control, MFA, and access reviews. That overlap causes procurement confusion because the same words show up in product brochures.

The difference is timing and intent. IAM uses MFA to protect sign-in. PAM often uses step-up verification at the moment of elevation. IAM uses RBAC to grant application access. PAM uses RBAC to define who can request privilege and which systems they can touch during elevated sessions.

Furthermore, privileged users still depend on good IAM hygiene. If the identity directory stays messy, PAM becomes a security bandage over an operational wound.

When IAM is enough and PAM adds marginal value

Some environments do not need a heavy PAM program right away. If your organization runs mostly SaaS tools and has few admin surfaces, strong IAM can cover the majority of risk. If you enforce MFA, you remove stale accounts quickly, and you keep roles lean, then you may not need session recording and vaulting on day one.

Still, do not confuse “not yet” with “never.” If you cannot list your privileged accounts and endpoints, you do not have a PAM problem first. You have an inventory problem first.

When you need both PAM and IAM (the non-negotiable scenarios)

You need both IAM and PAM when privileged actions can materially change business outcomes.

- You manage infrastructure like Windows, Linux, network gear, databases, or virtualization. Domain-admin equivalents and root access demand more than baseline login controls.

- You run cloud and Kubernetes. Cloud admin roles and cluster-admin privileges can create new identities, rewrite network policy, and mint fresh credentials. That means one compromised admin session can become a long-lived breach.

- You have audit pressure from regulators, customers, or cyber insurers. “We think only admins had access” does not satisfy an investigation. Evidence does.

- You depend on vendors. Third-party access should be time-boxed, monitored, and revocable without chasing shared passwords.

A practical decision framework

Ask these questions and answer them with real numbers:

- How many accounts can change production configurations today?

- Do privileged credentials exist in scripts, wikis, or engineer laptops?

- Can you show who performed a sensitive change within a few hours?

- Do admins use separate accounts for admin work?

- Can you enforce time-bound privilege for critical systems?

If those answers feel uncomfortable, you do not just need better IAM. You need PAM layered on top of IAM.

How to deploy PAM and IAM together without chaos

Start with IAM as the identity backbone. Centralize sign-in, enforce MFA, and automate provisioning and offboarding. Then add PAM where it matters most: your “crown jewel” systems and the identities that can alter them.

Prioritize reducing standing privilege. Use separate admin accounts, require approvals for production, and implement just-in-time elevation. Integrate access requests with ticketing, then forward PAM and IAM events into centralized logging. That prevents the classic failure where PAM becomes a parallel universe nobody monitors.

Conclusion: choose layers, not labels

PAM vs IAM becomes simple when you treat them as complementary controls. IAM scales trust decisions across the organization. PAM contains and documents high-impact actions. Together, they reduce both the likelihood of compromise and the blast radius of inevitable mistakes.

Next steps

- Inventory privileged accounts, endpoints, and automation secrets.

- Tighten IAM basics: MFA, offboarding, and least privilege roles.

- Roll out PAM to the highest-impact systems with just-in-time access and strong auditing.