Docker looks like this giant toolbox at first. Half the tools have names you’ve never heard. The other half feel like the same thing with different flags. If you’re a beginner dev, that’s a rough welcome.

So let’s simplify it.

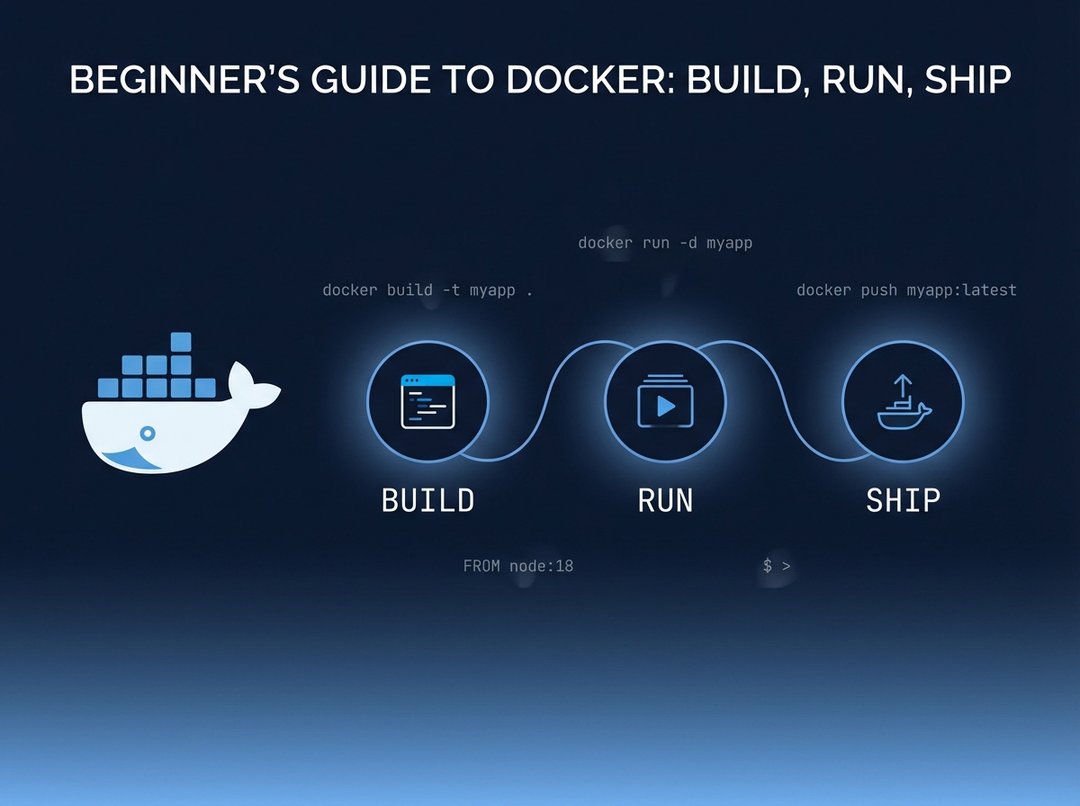

This guide teaches Docker for beginners using a tight loop you can repeat anytime: build an image, run a container, ship the image. Minimal commands. Real results.

Why Docker feels confusing at first (and what to ignore)

Docker dumps a lot of vocabulary on you fast. Images, containers, registries, volumes, networks. You try to learn it all at once. Then you forget everything after lunch.

Here’s what to ignore for now: Swarm, fancy networking modes, custom runtimes, and deep security tuning. They matter later. They do not help you ship your first app today.

You only need one clean mental model:

- Image: a packaged blueprint of your app and its environment.

- Container: a running instance of that image.

And one warning that saves a lot of pain: don’t treat containers like tiny VMs. You don’t “log in and patch” them. You rebuild the image and restart the container. That’s the whole point.

Docker’s three moving parts in plain English

- Docker Engine runs containers on your machine.

- A Dockerfile tells Docker how to build your image.

- A registry stores images so other machines can pull them. Docker Hub and GitHub Container Registry both work.

Minimal command set for Docker for beginners (the tiny toolkit)

If you remember only six commands, you can do real work.

The six commands you’ll use constantly

docker buildbuilds an image from a Dockerfile.docker runstarts a container from an image.docker pslists running containers.docker logsshows what your app printed.docker execruns a command inside a running container.docker stopstops a running container cleanly.

Everything else is either cleanup or convenience.

Optional but practical next layer

docker pullanddocker pushfor registries.docker rmanddocker rmifor deleting containers and images.docker compose uponce you have more than one service.

Build: your first image with a minimal Dockerfile

The build step is where Docker starts paying rent. You encode your environment once. Then every machine runs the same thing.

A beginner friendly Dockerfile has a few jobs:

- pick a base image

- copy your code in

- install dependencies

- define how the app starts

Here’s a small example for a Node app. Keep it as a reference. Tweak it for your project.

FROM node:20-slim

WORKDIR /app

COPY package*.json ./RUN npm ci

COPY . .EXPOSE 8080

CMD ["npm", "start"]

A couple details matter more than they look:

WORKDIRkeeps paths consistent. You avoid “where am I” mistakes.- Copying

package*.jsonbefore copying everything else helps Docker cache layers. Rebuilds get much faster. CMDdefines the default start command for the container.

Build command pattern you’ll reuse

docker build -t myapp:dev .

That -t gives your image a name and tag. Think “label.” myapp is the name. dev is the version.

Conceptual diagram: build pipeline in your head

Picture it like this:

- Dockerfile + your folder → build context

- Build context → layers

- Layers stacked → image artifact

If nothing changed in a layer, Docker reuses it. That’s why ordering your Dockerfile matters.

Run: start the container and see it working

Now you take that image and run it.

The one docker run shape that matters

docker run --rm -p 8080:8080 myapp:dev

What this does:

-p 8080:8080maps a port from your laptop to the container. Left side is host. Right side is container.--rmdeletes the container when it exits. That keeps your machine clean.

If your app listens on a different internal port, match that right side. If your laptop port is busy, change the left side.

Troubleshooting that actually works

Problem: “It’s running but I can’t reach it.”

Check ports first. Your app might listen on 3000 inside the container while you mapped 8080.

Problem: it exits instantly.

Read logs before you guess.

docker ps

docker logs

Logs usually tell you exactly what happened. Missing env var. Port binding error. Crash on startup.

Problem: you need to inspect the container.

Use exec for a quick look.

docker exec -it <container> sh

This is for debugging. You are not meant to live in there.

Ship: push your image to a registry with minimal ceremony

“Ship” means another machine can run your image without your codebase. That’s it. You build once. You distribute the artifact.

Docker Hub is simplest for beginners. GitHub Container Registry is great if you already use GitHub.

Tagging an image like you mean it

First tag it with a registry friendly name.

docker tag myapp:dev yourname/myapp:0.1

Avoid relying on latest as your only tag. It blurs history. Version tags keep you honest.

Login, push, verify

docker login

docker push yourname/myapp:0.1

Later you can pull it on another machine.

docker pull yourname/myapp:0.1docker run --rm -p 8080:8080 yourname/myapp:0.1

That pull-and-run is the real “shipping” moment.

The two concepts that prevent beginner pain later: volumes and env vars

This is where most beginner Docker setups crack. Not because Docker is hard. Because state and configuration are sneaky.

Volumes: keep data when containers die

A container filesystem is disposable. Stop the container and that local state goes away with it.

Volumes let you persist data outside the container lifecycle. In development you might use bind mounts. In longer lived setups you use named volumes. The key idea stays the same. You separate runtime from data.

Environment variables: configure without rebuilding

Hardcoding config into your image feels convenient. It also forces rebuilds for every environment.

Use environment variables instead. Pass them at runtime when needed. That keeps the image portable.

When minimal commands stop being enough: Docker Compose, gently

The moment you add Postgres, Redis, or a queue, typing multiple docker run commands gets old. Compose gives you one repeatable startup.

You can think of it like this:

- services are containers

- they share a network automatically

- volumes persist data

- ports expose what you need

The workflow stays simple:

docker compose updocker compose down

Compose is not “advanced Docker.” It’s the practical way to run multi container projects.

Common Docker for beginners mistakes (and clean fixes)

- Rebuilds are slow every time.

- Reorder your Dockerfile. Copy dependency files first. Let caching work.

- Images are huge.

- Use

slimbase images when possible. Avoid leaving build junk behind. - Paths break in containers.

- Set

WORKDIR. Use absolute container paths consistently. - Containers cannot talk to each other.

- Use Compose or a shared network. Do not rely on localhost between containers.

Quickstart checklist: Build, Run, Ship in under 10 minutes

Build

- Write a Dockerfile with a clear

CMD. - Run

docker build -t myapp:dev .

Run

- Run

docker run --rm -p 8080:8080 myapp:dev - Use

docker logswhen anything looks weird.

Ship

- Tag:

docker tag myapp:dev yourname/myapp:0.1 - Push:

docker loginthendocker push yourname/myapp:0.1

If it breaks

- Verify the port mapping.

- Read logs before changing code.

- Confirm the container is actually running with

docker ps. - Rebuild only after code or dependencies changed.

Docker for Beginners, now you can repeat the loop

That’s the core workflow. Build an image. Run a container. Ship the image.

And once that loop feels normal, Docker stops being “that scary ops thing.” It becomes what it really is. A clean, repeatable way to run your app anywhere.