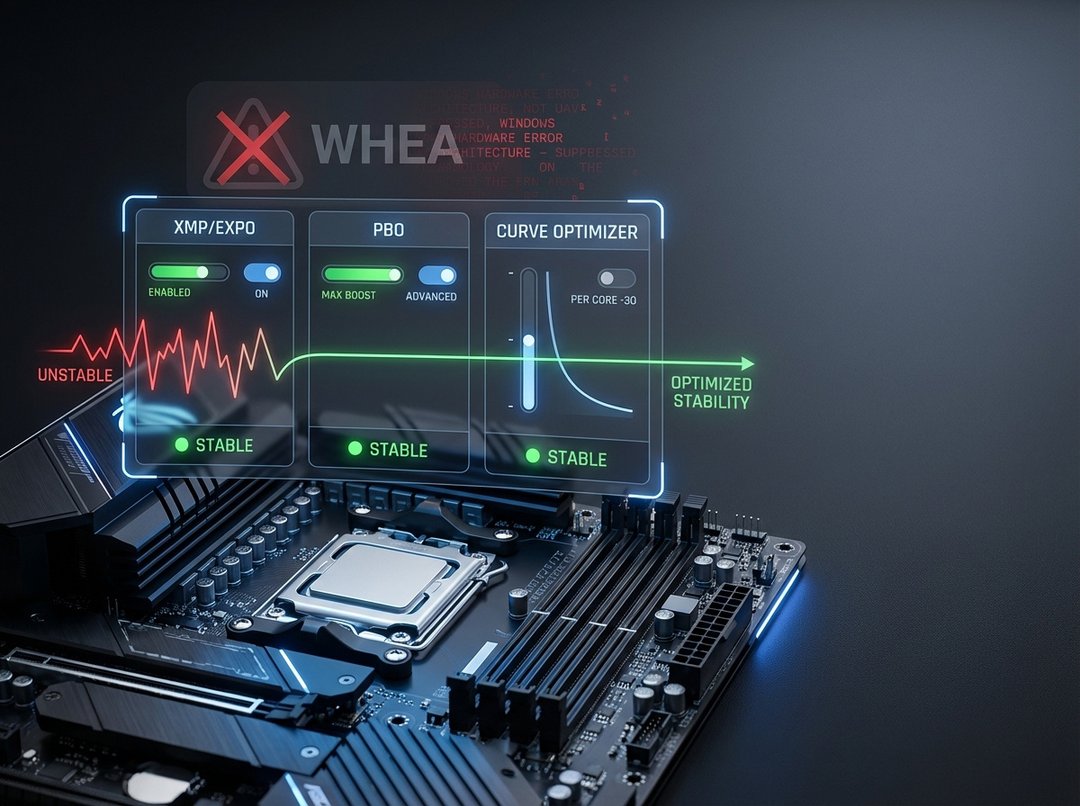

Modern BIOS tuning feels like walking a tightrope in work boots. One moment your system benchmarks like a hero. The next moment a game dumps you to desktop or Windows throws a WHEA warning like it has seen things.

This guide breaks down BIOS tuning for stability with a stability-first method. It explains XMP, PBO, and Curve Optimizer in the way enthusiasts actually need. Practical, technical, and structured so you can isolate variables instead of chasing ghosts.

Why “Stable” Systems Fail After “Safe” BIOS Tweaks

Most instability does not come from a single setting. It comes from stacked assumptions.

Enable XMP and you stress the memory controller. Enable PBO and you change transient current behavior. Add a negative Curve Optimizer and you shrink voltage margin right when single-core boost spikes. Each change seems reasonable alone. Together they can create a narrow failure window that only appears in certain games, at idle, or after heat soak.

Treat stability like engineering, not folklore. Change one variable. Validate. Then move on.

Before You Touch Anything: Establish a Stability Baseline

A stability-first baseline sounds boring. It also saves hours.

Start by updating your BIOS only when it matters. New AGESA or microcode often improves DDR5 training and boosts compatibility. But a “latest for the sake of latest” update can also change default voltages and memory behavior. After any BIOS update, load optimized defaults. Then re-enter settings manually. Old profiles can carry forward values that no longer map cleanly.

Next, document your starting point. Write down BIOS version, CPU model, RAM kit part number, and cooling setup. Note whether you run two DIMMs or four. That detail matters because memory topology changes signal integrity. Finally, confirm thermal reality. Watch CPU package temperature and hotspot behavior under sustained load. Heat changes electrical margin. Margins decide stability.

XMP Explained for Stability (And Why It Is Not Free Performance)

XMP loads a vendor-tested memory profile that runs beyond JEDEC defaults. On Intel it is literally called XMP. On AMD you will also see EXPO. The concept stays the same. You trade relaxed universal settings for tuned speed and timings.

XMP-related instability has a signature. The system may boot fine then crash under mixed workloads. Memory training may loop. You may see sporadic application failures that look like driver issues. On some AMD systems, you might also notice WHEA warnings when the memory controller or fabric runs close to its edge.

The stability levers are frequency, timings, and voltage. Frequency increases signaling demands. Tight timings reduce slack. Voltage can stabilize but it increases heat and long-term stress. Populating four DIMMs usually reduces the maximum stable frequency compared to two DIMMs. Dual-rank kits can behave differently than single-rank kits.

A stability-first XMP process works best:

- Enable XMP or EXPO with no other tweaks.

- If instability appears, reduce memory frequency one step before touching timings.

- If you still see errors, adjust DRAM voltage conservatively within the kit’s safe range.

- Only then loosen primary timings if needed.

Validate the result with a layered approach. Quick memory tests catch immediate faults. Mixed CPU and RAM loads catch borderline behavior. Real workloads matter most. If your crashes happen in games, you need a long gaming session. Stability must match how you actually use the machine.

PBO Explained for Stability: Boosting Without the Chaos

PBO, or Precision Boost Overdrive, expands AMD boosting behavior beyond stock limits when there is thermal and power headroom. It can deliver real performance. It can also expose silicon and motherboard margins.

Think of PBO as a set of guardrails. The important ones are PPT, TDC, and EDC. PPT caps sustained package power. TDC caps sustained current. EDC caps burst current. EDC often drives the “spiky” behavior that creates instability during rapid load changes. Those spikes can push a core into a frequency point that needs more voltage than your settings allow.

Stability-first PBO tuning should stay disciplined. Start with PBO enabled while keeping boost override at zero. Confirm stability under your real workloads. Then raise limits modestly if temperatures and VRM behavior stay controlled. Avoid aggressive scalar values early. Scalar extends time spent at higher voltage. More voltage can help stability in some cases. It also increases heat and stresses the same margins you are trying to protect.

Curve Optimizer Explained: Undervolting That Does Not Backstab You

Curve Optimizer changes the voltage-frequency curve per core on many Ryzen CPUs. Negative values reduce voltage for a given frequency. That can lower temperatures and increase boost headroom. It can also trigger the most annoying instability of all. The random reboot while you are doing nothing.

Here is why. Light loads often boost higher than heavy loads. A system might pass a heavy multi-core test. It can still fail during bursty single-core boosts, idle transitions, or sleep-wake cycles. Also, each core has a different quality level. One core may tolerate a deep negative curve. Another core may crash with a mild value.

Enthusiasts get better results with per-core tuning. An all-core negative offset is fast but it hides weak cores. With per-core values, you give strong cores more negative headroom. You protect weak cores with gentler settings. That approach preserves performance and stability.

When you tune, validate with both heavy and light patterns. If you only run a sustained render test, you miss the burst behavior that triggers many Curve Optimizer failures.

The Sequencing Rule: Do Not Combine XMP, PBO, and Curve Optimizer Too Early

This is the rule that separates methodical tuning from superstition.

Use this order for BIOS tuning for stability:

- Stock baseline stability.

- XMP or EXPO stability.

- PBO stability.

- Curve Optimizer stability.

- Final validation with everything enabled.

If the system fails after stacking changes, unwind in reverse. Disable Curve Optimizer first. Then reduce PBO aggressiveness. Then step down memory frequency. This sequence isolates root cause faster because each layer has a distinct failure mode.

Advanced Guardrails: Voltage, LLC, and the WHEA Canary

Voltage tuning attracts strong opinions. Some of them are wrong.

More voltage can stabilize memory. It can also raise temperatures enough to destabilize boost behavior. That is why single-variable changes matter. Make one adjustment. Retest. Document.

LLC, or load-line calibration, matters because it changes voltage droop under load. Too aggressive LLC can create overshoot. Overshoot can destabilize just as easily as droop. Too weak LLC can droop into crash territory during transient spikes. Auto settings can also misbehave. Some boards apply optimistic voltages when you enable XMP or PBO. Those “helpful” boosts often increase heat while masking the true margin.

Finally, treat WHEA warnings as an early alarm. They often indicate borderline hardware stability even when the system “seems fine.” If you see repeated WHEA entries after tuning, do not ignore them. Pull back the most recent change and revalidate.

For deeper vendor context, start here: Intel’s XMP overview and AMD’s boost documentation.

- https://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/gaming/extreme-memory-profile-xmp.html

- https://www.amd.com/en/technologies/ryzen-master

Practical Stability Checklist When It Still Crashes

When crashes persist, match symptom to first move.

- Memory-related errors or training loops: drop RAM frequency one step, then retest.

- Reboots under heavy load: reduce EDC or remove any boost override.

- Idle or desktop reboots: lessen negative Curve Optimizer values on best cores.

- Crashes after long sessions: reduce PBO limits or improve cooling curves.

The best stability tuning feels almost dull. One change at a time. Same test each run. Notes like a lab notebook. That discipline turns “random crashes” into solvable causes.

Stable BIOS Tuning That Keeps Performance

BIOS tuning for stability works when you treat XMP, PBO, and Curve Optimizer as a chain of dependencies. XMP defines memory behavior. PBO defines boost aggression and current transients. Curve Optimizer defines per-core voltage margin. Tune them in that order. Validate each layer. Then enjoy a fast system that behaves like it should.

Fast is fun. Stable is freedom.